As a young man, the Swiss writer Robert Walser wanted to be an actor. In 1895, having fled a bank apprenticeship, he followed his brother, Karl, to Stuttgart, moving into an attic room across from the Royal Court Theater. A humiliating appraisal at the hands of another actor laid bare his inadequacies. The encounter is depicted in several later stories. (“You possess not the faintest trace of theatrical talent,” one doyenne concludes. “Everything about you is hidden, veiled, buried, dry, and wooden.”) That this great literary dissimulator should lack dramatic ability is one of the many appealing paradoxes Walser inhabits. But however unfit for the stage, he never abandoned the actor’s sense of improvisation. Even then, while yet a teenager, he disclosed a willingness to transform. “There isn’t going to be any acting career,” he wrote to his sister, “but if God so wills it, I am going to become a great writer.” For Walser, the difference between the two professions was negligible. In the ensuing decades, his life and writing would become their own kind of thrilling performance.

Walser’s brilliant short fictions ally him with Erik Satie, Paul Klee, and the other gifted miniaturists of modernism. The Walserian mode is elusive, gentle, courteous, submissive, youthful, disarming, and genial. His unassuming protagonists—students, artists, servants, and children—are poets of inconspicuousness and locality. They are impish and somehow otherworldly, petit-bourgeois sprites saddled with classes and clerkships, making suspiciously cheerful meaning of their own disenchantment. But this innocence is one of twentieth-century literature’s most sophisticated acts of legerdemain. The smaller, the more picturesque, the more seemingly guileless the narrative form, the more tightly Walser coils his lacerating ambiguities. Infinitely light and impossibly dense, his short prose works are gorgeous confinements out of which some radiant and contradictory energy is forever threatening to escape.

He has been embalmed in lurid rumor. Nothing has yet managed to displace the legend of the perambulating crank, a sexless, hard-drinking oddball who walked twenty miles a day, heard malicious voices, wrote from the shrinking world of the “pencil territory,” spent two decades in an asylum, and died while out walking on Christmas Day. (An iconic photograph, shot by the local constable, shows him lying in the snow. The footprints end some distance before the body, as if he had managed to float part way into eternity.) The cult of Walser is sustained by seductive illusion, a relationship cannily understood by the writer himself. “My vocation, my mission, consists mainly in making every effort to keep my audience believing I am truly simple,” he wrote in 1925. But the irresistible romance of his art brut bona fides has come to obscure the rigorousness of his anti-commercial craft.

Susan Bernofsky’s “Clairvoyant of the Small: The Life of Robert Walser,” the first English-language biography of Walser, looks to dispel the fantasy of the idling, half-mad naïf. (The title is taken from one of Walser’s many admirers, W.G. Sebald: “He is no Expressionist visionary prophesying the end of the world, but rather a clairvoyant of the small.”) Bernofsky, a professor and distinguished translator of German literature, situates Walser’s eccentricity, reticence, and melancholy within a life of exemplary literary discipline. He comes across, first and foremost, as a tireless worker: living by his pen, badgering editors for advances, and enduring terrible austerity for his art. Bernofsky’s welcome corrective is exhaustively researched, though necessarily fragmentary. Given the relative scarcity of surviving letters during certain periods, Walser’s semi-autobiographical fictions are marshalled to fill in the gaps. What emerges from the record is a tantalizing chiaroscuro: flashes of life and work offset by shadowy lacunae.

Walser was born on April 15, 1878, to middle class parents, in Biel, Switzerland. His father, Adolf, a descendent of pastors and intellectuals, ran a general store specializing in toys and costume jewelry. His mother, Elise, a more significant presence in Walser’s imagination, suffered from crippling bouts of depression and rage. There is something fabulous and cursed about the eight Walser children. They are like figures from a fairy tale or play, mythic and prone to dazzling or tragic circumstance. The eldest brother died at fifteen; another preceded Robert into the Waldau asylum; another committed suicide; another, Robert’s best friend, Karl, was a celebrated illustrator, lothario, and stage designer for Max Reinhardt. His sister, Lisa, on whom he came to increasingly depend later in life, became a teacher in a mountain village. As the second youngest, Robert early on developed a keen understanding of the hierarchies that would animate his mature work. His acts of brotherly renunciation were in reality sly consolidations of power. This deceptive submissiveness can be found in many of his protagonists, who well understood what Bernofsky calls “the hidden power of the subservient.”

He left school at fourteen to apprentice as a bank clerk. The commis or bookkeeper, that modern, ink-stained figure of comic paradox that so intrigued Gogol, Melville, and Kafka, would become a fixture of his later fictions. After his dramatic failure in Stuttgart, he moved to Zurich in 1896, where he would live for almost a decade in a series of furnished rooms. His proto-Expressionist poetry first brought him to the attention of the public, though it would be his 1899 prose debut, the sinuous feuilleton “Lake Greifen,” that suggested the writing he would become known for.

The short prose piece is Walser’s essential narrative unit. His is a world of fables, travelogues, essays, idylls, meandering critical pieces on painting and theater, fantasies, dramolettes, and uncanny extemporizations. Their snow globe titles (“Little Snow Landscape,” “Two Little Fairy Tales,” “The Carousel”) and bejeweled surfaces belie the totalizing irony that awaits the reader. Subjects are effaced by way of endless refinement and qualification. Insignificance is embroidered with impossible verbal finery. Themes disintegrate, only to reform later with strange, totemic significance. The velocity and mutability of his observations are finally comic. Walser casts himself as a sort of alpine Buster Keaton, his slapstick energy palpable even as the set crumbles around him. He often relies on some pleasing foundational misdirection, as in “Vacation,” which begins: “The waves splash in the bay. Surely I’m lying when I claim this, but we do say anything to get something going.”

But there is an unplaceable torment in Walser. He is capable of abrupt, disfiguring bitterness, often delivered in deadpan volte. “The Factory Worker,” an otherwise gentle and lilting bit of nested fiction, terminates in sudden catastrophe, the onset of war worthy of no more than a caustic shrug: “who knows, perhaps the worker was amongst those who fell for the Fatherland.” These shelves of ice in the meadows of Walser’s world obstruct its traversal. For all of the postcard quaintness of his pastoral fantasies, they have about them a whiff of the demonic. Their frivolity disguises some permanent dislocation. To be compelled to make light of one’s desolation and absurdity is a punishment worthy of the damned. In these comedies of spiritual incomprehensibility, the laughter is never very far from a terrifying, runaway hysteria.

After the publication of his first novel, 1904’s “Fritz Kocher’s Essays,” a collection of short pieces masquerading as a precocious child’s notebook, Walser felt ready to take on Berlin. There he moved in with his brother Karl, whose artistic success granted Robert access to the city’s rich vein of Secessionist bohemian life. As in his sometimes whimsical fictions, Walser was not above acting the fool for his cosmopolitan friends. It was a version of himself he seemed to enjoy, the handsome yokel and rabble rouser, drinking heavily, flirting, eating too much at dinner parties, and insulting other writers. (He and Karl once chased the playwright Frank Wedekind into a café with shouts of “Muttonhead!” Wedekind never spoke to them again.) He enrolled in butler school to shock Karl’s wealthy patrons and spent an autumn in the employ of a Silesian count.

The European novel was then in the midst of its great internal emigration. Works like Robert Musil’s “The Confusions of Young Törless” and Rainer Maria Rilke’s “The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge” featured young, disoriented protagonists exploring perilous inner worlds. Elsewhere, in Prague, Kafka was just beginning to document his dreamlike inner life. Walser’s free-floating fictions, pocket soliloquys suggesting an impenetrable private terrain, placed him at the forefront of this imaginative vanguard. Though his triptych of Berlin novels began in realist territory—“The Tanners,” published in 1907, nakedly dramatized the lives of the Walser brood; “The Assistant,” appearing a year later, was based on his apprenticeship to an inventor in Wädenswil—a great shift occurred with 1909’s “Jakob von Gunten.” With it the modernist novel plunged into bottomless ambiguity.

Walser’s favorite among his longer works, “Jakob von Gunten” purports to be the diary of a young man enrolled in a school for servants. The eponymous hero has run away from his aristocratic family, intent on becoming “a charming utterly spherical zero.” At the Benjamina Institute, he discovers a curious pedagogical limbo. Its teachers “are asleep, or they are dead, or seemingly dead, or they are fossilized, no matter, in any case we get nothing from them.” There is only one class: “How should a boy behave?” The entire operation is run by a mysterious brother and sister whose private chambers delineate a remote world every bit as tantalizing and fantastical as Kafka’s “The Castle.” The novel proceeds with a shimmering, oneiric quality. Jakob, a figure of indolence and mock-solemnity, thrives in this unfixed environment. He slowly gains ascendancy over the Benjamentas, humiliating and exalting them in equal measure. His motives for doing so remain inscrutable. Akin to an allegory sprung free of its meaning, the novel finally rejects both aspiration and submission alike. “How fortunate I am,” Jakob writes, “not to be able to see in myself anything worth respecting and watching! To be small and to stay small.” As the meticulous labor of his writing demanded an ever more circumscribed way of life, this mantra of diminution could have been Walser’s own

For all their sophistication, these remarkable novels made no discernible difference to Walser’s material condition. Broke and homesick, he returned to Switzerland in 1913, spending the next seven years in the attic of a temperance hotel in Biel. Though ambivalent about the war, he was called up several times—mainly to dig trenches and build fortifications—while maintaining an intimate correspondence with a laundress. (“Writing each other letters is like gently, carefully touching,” he wrote.) His prolific run of short fiction during this middle period is marked by its stylistic turn toward recursiveness. In stories like “The Sausage,” “Basta,” and “Well Then,” the spiraling repetitions of postwar formalists like Thomas Bernhard can be discerned. Despite this ambitious evolution, his audience and income diminished. Two novels, “Tobold” and “Theodor,” were lost or abandoned. A third, “The Robber,” an extravagant and sexually anxious work of deferment, would not be published until 1972. These abdications have about them a sense of willed reprieve. To write such works only to render them unavailable is an eminently Walserian gesture. His exploding ambition conspired with his shrinking life to produce a secret, vanishing literature. This was one way to free himself from fear of failure and the commercial grind: to consign particular works to oblivion. He would later write to Max Brod, in 1927, “Every book that has been printed is, after all, a grave for its author, isn’t it?”

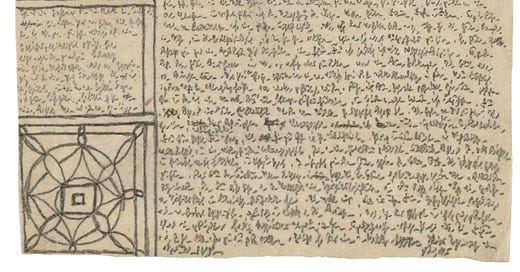

After experiencing psychosomatic hand cramps, he developed a new form of composition commensurate with his narrowing circumstances. This abbreviated script, one to two millimeters in height, was written in the medieval German he preferred. Long considered to be indecipherable, or else a kind of private code, an entire story could fit on a business card or rejection slip. (He wrote on any surface available to him.) The secretive and provisional nature of his micrography—what he called the “pencil method”—ensured a private world of experimentation could exist outside the pressures of publishing. Combining necessary thrift with a need for seclusion, this miniaturization was, as Bernofsky has it, “an instinctual gesture of self-preservation.” It was also a rehearsal for a more permanent form of disappearance. The great silence of Herisau awaited, though not before the final flourishing of his mature style and its lush, fractal complexity.

Walser’s prose of this period—1925 to 1929—constitutes a new and remarkably baroque vision. It was as if, freed at last of his increasingly tenuous connection to the nineteenth-century realists that inspired him, he was free to become the avant-garde maximalist he knew himself to be all along. Neologisms, compounds, and abstract nouns proliferate helplessly, as in “The Robber,” whose many florid coinages includes the charming “littledaughterlinesses.” Layered puns introduce uncertainty to even the simplest of actions. Walser’s sentences, too, explode with arabesque complication. Sub-clauses intervene or obstruct rather than clarify, inviting sleek threads of digression. The slalom-like momentum of each sentence provides the drama usually offered by character or action. These techniques turn signification itself into a shape-shifting game. The primacy of artifice becomes Walser’s grand, late subject, a fitting capstone for modernism’s most unfathomable ironist.

In 1929, Lisa Walser, on the advice of a trusted doctor, brought her brother to the Waldau asylum. Fearful and hearing voices, he had recently made marriage proposals to both his landlords before asking them to stab him to death. His admission form listed him as schizophrenic, though the facts of his illness render this diagnosis unpersuasive. (Depression or bipolar disorder seems more likely.) A compliant if aloof patient, he spent his time working in the garden, shooting billiards, and writing poetry. There is a sense of him playing the invalid, as he had played the butler, his submission to routine a relief after the long unraveling in Biel. This equilibrium collapsed when Waldau’s new director deemed him well enough to reenter the world. Walser refused, and was forcibly transferred to Herisau’s Cantonal Asylum in 1933. What we know of Walser during these years comes from Carl Seelig, a critic and editor who befriended him and later became his legal guardian. (His book, “Walks with Walser,” recorded their conversations on art and life.) It was to Seelig that Walser supposedly delivered his infamous, puckish assertion: “I am not here to write, but to be mad.”

That this pithy, atmospheric, and oft-quoted line should be apocryphal—and it assuredly is—suggests the troublesome stickiness of the Walser mystique. The romantic image of the outsider artist going mad amid his tiny scraps of paper leaves no room for the reality of the ascetic craftsman. Bernofsky’s book extends the grace of adjusted proportion to its subject. It moves Walser’s oddity and muscular ambition into cohabitation. A gifted and longstanding translator of his work, her critical unpacking of Walser’s novels and stories is itself an act of oblique narrative. Rather than shed light on the tortuous life, his fiction’s proximity to autobiography somehow obscures it. He is forever backlit, a striding silhouette. “No man is entitled to act toward me as if he knew me,” one of his child-avatars says. Bernofsky would never presume to. By book’s end, Walser’s resistance becomes an unlikely dimension of intimacy. He eludes in the manner of those we feel we know best and end up misunderstanding completely.

After arriving at Herisau, Walser never published again. What writing he may have accomplished while institutionalized remains shrouded in mystery. According to two staff members, he would often write after meals while standing at a window ledge, hiding his work if anyone drew near. When he died, his coat pockets were found to be filled with letters and pay stubs—future palimpsests, perhaps, for the “torn-apart book of myself” he’d been writing since that failed audition in Stuttgart.

“a sort of alpine Buster Keaton” -- brilliant.

Beautiful essay. Ordered Jakob von Gunten immediately.